Peer-to-Peer Lending: Business Model Analysis and the Platform Dilemma

Eugenia Omarini A*

Department of Finance, Bocconi University, Via Roentegen, Milano, Italy.

*Corresponding Author

Anna Eugenia Omarini,

Department of Finance, Bocconi University,

Via Roentegen, Milano, Italy.

Tel: 0039(02)5836

E-mail: anna.omarini@unibocconi.it

Received: August 01, 2018; Accepted: September 24, 2018; Published: September 29, 2018

Citation: Eugenia Omarini A. Peer-to-Peer Lending: Business Model Analysis and the Platform Dilemma. Int J Financ Econ Trade. 2018;2(3):31-41.

Copyright: Eugenia Omarini A© 2018. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Online peer-to-peer lending is a growing industry with huge potential for capturing customers from mainstream financial institutions and therefore setting a new standard for loan requests and for creating an additional investment opportunity. To get some benefits from this growth, companies operating in this industry should develop a resilient business model that aims at attracting the greatest number of lenders out of the whole lenders’ population and the greatest number or borrowersout of the whole borrowers’ population.

The growth of online lending will accelerate in the next years, under certain conditions, and this can be true if they take care of both investors and borrowers’ needs. The aim of the paper is to investigate the P2P outlining the importance of being a platform business model. The paper is structured as follows: in paragraph 1. It is given a brief description of Fintech, Crowdfunding and Peer-to-Peer (P2P) lending. Then paragraph 2 and related outline the main features on the way platforms perform their activity as well as the types of loans transacted. Paragraph 3 and related describe the issue of being a platform for a P2P business. In paragraph 4 the main conclusions and managerial implications are outlined.

2.Abbreviations

3.Introduction

4.A Framework of Definitions in the Peer-to-Peer Lending Landscape

4.1 Types of loans transacted in a nutshell

4.2 The market size

4.3 Description of Fintech credit activity

5.The Issue of being a Platform

5.1 From “attraction” to “extraction”: the logical steps in P2P lending platforms

6.Conclusions and Managerial Implications: The Platform Dilemma

7.References

Keywords

Digital Transformation; FinTech; Techfin; Retail Banking; Business Model; Open Innovation; Platform.

Abbreviations

P2P: Peer To Peer; IDPS: Investor Directed Portfolio Services; RWA: Risk Weighted Asset.

Introduction

Peer-to-Peer (P2P) lending can be defined as a “financial exchange” that occurs directly between individuals without a direct intermediation of a traditional financial institution. Banks still play a role, as given by regulation, they act as depositary institutions, used to provide platforms with accounts where money is deposited, and put it at the disposal of the platform. The main idea is that peer-to-peer lending is in fact no different to what’s been happening in families and communities for centuries all around the world. Peer-to-peer lending communities can be traced back to 1630s and 1640s, years in which were first born the so-called Friendly Societies in Britain. These organizations featured many of the characteristics of the contemporary peer-to-peer lending communities. Upon registration, these societies granted privileges to its individuals, which often translated into mutual support and financial assistance. As contemporary peer-to-peer communities, Friendly societies membership was mainly working-class, something that helped people to construct the solidarity thought necessary to achieve successful collective action. While in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries societies became more and more individualistic, Friendly Societies maintained their spirit and their commitment to mutual support, also incorporating the emerging concept of self empowerment, typical of the middle-class of that age (Hulme, 2006). It can therefore be stated that the concepts of community and collective advantage have resisted throughout centuries and they are still characterizing the reemergence of the peer-to-peer lending phenomenon we are witnessing today. What has made peer-to-peer lending re-emerge in the 21st century is that now it can be carried out through Internet.

Given that above, Peer-to-Peer lending involves the matching of borrowers and investors via a web-based platform and the operator managing, as an agent for investors, the resulting repayment obligations of borrowers. P2P lending is a fast growing industry globally with the number of operators as well as the number of loans being issued increasing substantially over the last ten years. The USA and the UK have the most established P2P lending markets.

P2P lending is, in a number of respects, little different from other platform-based markets (such as AirBnB, Hotels.com, etc.), which enable buyers and sellers of heterogeneous goods and services to trade, with prices determined ultimately by demand and supply, through auction processes or fixed price offers. The enabling driver is the modern digital technology. However, there are some important differences, such as the following:

- P2P operators provide their own quality assessment of the product (loan) being offered - which is a form of financial advice.

- P2P operators manage (over several years) the subsequent physical delivery to the purchaser (investor) of the obligations (interest and principal repayments) of the vendor (borrower) - creating a principal-agent relationship.

- P2P operators provide purchasers with account management (financial) services (Investor Directed Portfolio Services - IDPS) enabling purchasing (and possibly subsequent resale) and custody of products (loan assets), and receipt (and possible reinvestment in new products, storage, or withdrawal) of cash receipts from products owned.

- P2P platforms (and associated services) are an example of a more general integration of provision of a number of economic functions made possible by the resembling of them throughout the presence of Fintechs in the financial ecosystem. The main interesting feature is that each function can be provided separately by separate entities. Specifically, P2P platforms combine the functions of a market (exchange) operator and a provider of financial services (individual account and trading facilitation) such as exemplified by stockbrokers (market participants). Of particular importance, Fintechs enable direct access to the market by endusers (without the need for broker - market participant involvement) and integrated provision of those functions listed above. This removes the distinction between market operators and financial service providers (market participants), which is a special case of non-integrated provision resulting from old technology. The main idea behind is that P2Ps enable a new and strong integration between a direct financial circuit - the market - and the indirect financial circuit - made by different financial intermediaries.

The aim of the paper is to investigate the P2P outlining the importance of being a platform business model. The paper is structured as follows: in paragraph 1 it is given a brief description of Fintech, Crowdfunding and Peer-to-Peer (P2P) lending. Then paragraph 2 and related outline the main features on the way platforms perform their activity as well as the types of loans transacted. Paragraph 3 and related describe the issue of being a platform for a P2P lending business. In paragraph 4, the main conclusions and managerial implications are outlined.

A Framework of Definitions in the Peer-to-Peer Lending Landscape

When talking about Peer-to-Peer lending it often happen to meet two other concepts, Fintech and Crowdfunding, which are highly related. In fact, Peer-to-Peer lending is part of Crowdfunding, which is in turn an area of the Fintech landscape.

According to Arner, Barberis & Buckley [1] the label Fintech entered the market as the employment of technology to provide financial services. Blake &Vanham [2] refer to Fintech as the use of technology with respect to the design and provision of financial services. In addition, PwC [3] describes the Fintech (contraction for Financial Technology) as the evolving intersection of financial services and technology. Another interesting definition describes Fintech as a technologically-driven process in the financial industry which introduces new working methods and approaches to standard processes [4].

Finally for a broader definition of Fintech it is interesting to look at the definition given by the Financial Stability Board [5], which describes Fintech as technologically enabled financial innovation that could result in new business models, applications, processes, or products with an associated material effect on financial markets and institutions and the provision of financial services.

Fintech companies are working to improve the customer experience and efficiency in financial operations, and these are the main reasons why they work on personalization, transparency and accessibility via digital channels, so that they may become an interesting alternative to traditional services provided by conventional financial institutions.

Moving forward, the term Crowdfunding is an innovative way of financing, but also offering a set of marketing tool, because it gives companies also the opportunity to be tested on the market and create a direct engagement with customers [6]. There are different forms of crowdfunding, which can be classified as follows:

1. Donation/philanthropic crowdfunding: funders donate for philanthropic purposes, especially to charities and nonprofit organizations, even though in practice also a profit-oriented company may participate to such an initiative. Funders donate for a cause they believe in and may be rewarded in a symbolic way, but not with a material prize. The risk connected with it is very low, because people cannot expect a return [6].

2. Reward/commercial crowdfunding: it finances artistic or innovative ideas and it is a method to finance a project or a product in its initial phase. It is also a marketing tool, to make early adopters know about a new product. In this case, people may be rewarded with non-monetary returns [6].

3. Royalty crowdfunding: the reward is monetary and consists in sharing the profits or revenues connected with the investment, but without any claim over the property of the project or over the reimbursement of capital.

4. Crowdinvesting: in this case, the financing operation is for investment purposes, thus it is associated with a remuneration. This category includes:

a. Equity-based crowdfunding, which is a direct form to finance companies, since entrepreneurs invest in order to get a share of the venture’s future earnings.

b. Lending-based crowdfunding: funders supply funds for a certain period, expecting to get the money back and a given interest. This form of crowdfunding is the most consistent.

c. Invoice trading, which consists in the transfer of a commercial invoice to obtain liquidity.

A recent trend in the EU market is the development of secondary marketplaces, to give lenders participating to the third and fourth type of crowdfunding the possibility to liquidate their investments whenever they want. Without that, people would hardly finance a project, because they know they could have liquidity problems requiring them to withdraw immediately the money invested. More over, the risks connected with this new tool can prevent them to try at all without the certainty of being able to stop investing [7].

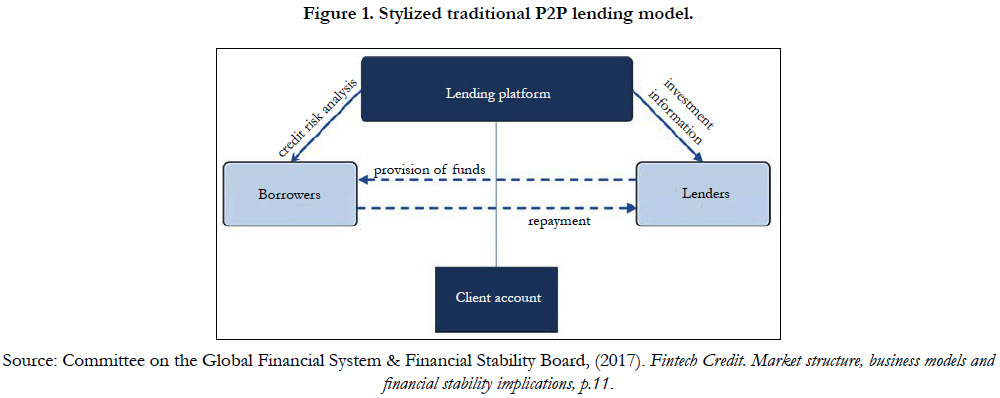

The further step is to give a definition of Peer-to-Peer lending (P2P), which might become an alternative to traditional financial intermediaries. In this way individuals/families and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) can be financed directly by different investors. Here, innovation is on developing the business model on an internet platform, making it easier to gather users, both from the lenders’ and the borrowers’ side. Money transactions undertake among unrelated individuals, or peers [8]. The mechanism on how it works requires the following steps (see Figure 1):

1. Both investors and borrowers subscribe in the platform;

2. Investors and borrowers’ information are verified and to each borrower is assigned a credit score;

3. The loan request is displayed on the platform, specifying all the conditions related to it;

4. Investors can decide where to invest: they can do that on their own or they can leave this step to the platform, only providing for some desired characteristics. The interest rate can be either provided by the platform, or decided by investors themselves;

5. Once the borrower’s request is totally funded, the conditions are shown;

6. The platform rules the money transactions between borrowers and lenders and intervenes in case there are delays in payments. Money is deposited on a physical bank account.

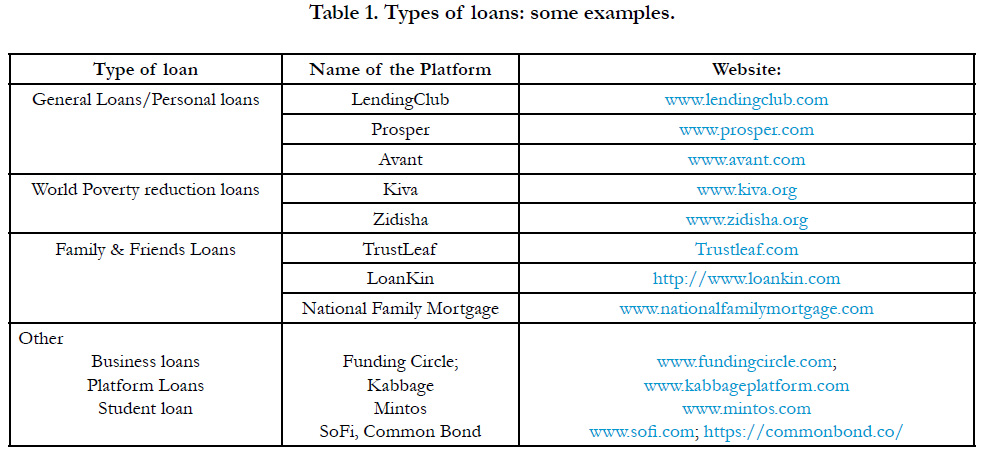

Considering the P2P lending industry, in its broadest definition, there are many platforms worldwide. To give a brief overview of this segment of the market, these platforms need to be grouped in four main categories, which have been defined according to the type of loan that is transacted on such platforms:

This is the biggest category of loans transacted by borrowers and lenders on online lending platforms. Upon payment of a fee by both borrowers and lenders, the company grants the possibility to lenders to meet borrowers online and exchange funds. These loans are considered unsecured loans as they are not backed by any collateral from the borrower’s side. The lending platform in addition to earning from fees, often sells complementary services mainly to borrowers, such as insurance products against illness or unemployment, the main causes of loan repayment impossibility.

The purpose of this category of loans is to alleviate world poverty. Usually loans are disbursed to citizens of third world countries, mainly to entrepreneurs given their higher ability to repay the loan. It is not fully appropriate to talk about peer-to-peer loans as it is not the borrowers directly who make the loan request (which is evident given the low web-literacy rate that third world countries experience). In fact, between the lender and the borrower there is usually an intermediary called Field Partner that is responsible for searching for local entrepreneurs with interesting business ideas and in need of funding. Usually the interest rate received by the lenders is set in advance and it is not as high as “general peer-to-peer loans”. The reason is that part of the interest payments made by lenders goes directly into the pockets of the Field Partners, which incur high costs to screen the potential borrowers. The online platform therefore screens the Field Partners rather than the borrowers themselves. Furthermore, many of these platforms are non-profit organizations and they receive a small part of the interest payment made by the lender, just to manage their infrastructure.

These types of loans are disbursed from one family member to another family member and they are usually run by the same rules that govern regular loans. Some online platforms were born precisely with the objective of servicing these types of loans. Both borrowers and lenders are part of the same family or group of friends and they have first of all to agree on the interest rate that the borrower should pay on the loan requested. Once this is set, the online platform intervenes to institutionalize the loan: it provides all the papers necessary to give to the loan a legal status, it ensures that all the payments are made, it provides help in case of missing payments; in few words the online company manages the loan in exchange for a fee. In some cases, these companies also sell additional products to the participants, such as special accounts or a loan that fills the gap between what required by the borrower and what offered by the lender.

There are three other types of loans: the first one is the “business loan”. In this case, the loan is often labelled as “p2c”, people to company, because the consumer lends to businesses directly. The second loan type is represented by a “platform loan”. In this case, it is the online peer-to-peer platform itself, which issues the loans to borrowers. In addition, the company also sells to investors some financial instruments (usually Certificates of Deposits, federally insured instruments saving certificates that ensure the payment of a constant interest rate and principal amount at a certain maturity date), which promise better financial returns, than those offered by banks. In exchange, the investor needs to participate to the payment of the loan instalments of any borrower at his choice, deciding the amount he wants to contribute. The third type of loan is represented by the “student loan”. The main purpose of this category of loans is to help students to accomplish their university studies without being financially constrained. Students usually list their borrowing requests on online communities, detailing for what precise activity or expense they will need that money. Usually the loan is co-signed by an adult (usually a parent) who ensures that the loan payments will be made on the due time. Then lenders decide to whom they should lend money and the amount they will grant to the chosen student. The strong advantage of these loans is that they allow deferred payments: the student/borrower will pay back the loan once he has graduated and started working. Only a small symbolic amount needs to be paid each month, just to show commitment to the loan. In this case, the online platform performs a screening on the borrowers, in order to minimize risk, and on the co-signers. Another interesting feature is that both the interest rate and the fees the borrower will end up paying depend on the academic performance of the borrower itself. Lenders instead pay a fixed annual fee just to cover the costs of the monthly transaction the platform needs to ensure.

In Table 1 is shown a set of examples of the main P2P lending companies categorized as above.

According to the report [9] the geographic distribution of P2P European platforms, excluding the UK where there are more than 40 of them, shows the highest concentration of such platforms in Germany (35), France (33), Spain (32) and Italy (26) and the Netherlands (19). While individually the Nordic Countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden) had fewer than 10 platforms each, the region recorded 32 participating platforms.

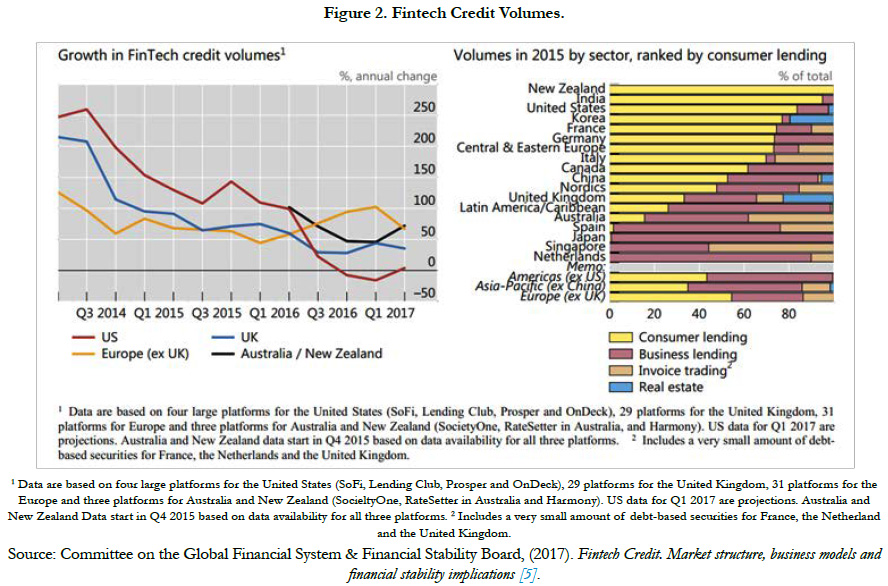

For the year 2015 the largest market is China (99.7 billion $), followed by the US (34.3 billion $) and the UK (4.1 billion $). In other countries, numbers are relatively small. Even though, the growth is incredibly quick, as shown by Figure 2. In the UK, which is the biggest European P2P market, Fintech credit was estimated to be 14% of gross bank lending flows to small businesses in 2015, but only 1.37% of consumer and small-business lending at the end of 2016.

On the left side of the graph, there has been a huge growth in the market between 2013 and 2015 (the chart shows the growth in percentage, thus a decline in the line highlights a decline in the growth, not a decline in the amount lent or invested). Two exceptions can be outlined, and they are: in the Nordics, there has been a decline in the growth, connected with the failure of the Swedish platform TrustBuddy (the new management team in 2015 found out signs of misconduct, since the platform was raising capital from investors only to cover bad debt and previous losses). In the US, on the other hand, it can be seen a clear decline between the end of 2016 and the beginning of 2017. This decrease only regarded the larger platforms, so that it can be linked to a loss in their market share. The right side of the chart shows the components of the Fintech business in each country. In countries such as the US, Germany, Korea, New Zealand and Italy, the biggest part of the market corresponds to consumer credit (in the US, student loans are the larger part of that). In other countries such as Australia, Japan and the Netherlands, the Fintech market is focused on business credit, comprising invoice trading. In the UK, business credit is the most developed, together with real estate credit. The latter segment is completely undeveloped in the other European countries.

The nature of FinTech credit activity varies significantly across and within countries due to the heterogeneity in the business models of each online credit platforms. Notwithstanding, any P2P lending platforms looks for providing a direct exchange between lenders and borrowers. Given that, an important issue regards the target market (which means having consumers versus business platforms), because they have different financial needs, amounts required and rating information.

Given that, it is interesting outline there are different ways to match borrowers’ and investors’ financial requests, and they are:

It is when the platform has an active role in both selecting loans applications and matching borrowers and lenders. The platform collects the money from each investor and allocates it on several loans, taking into account the guidelines given by investors - who can decide over the amount to lend, the expected return and the risk appetite, i.e. the level of risk expected from the portfolio. The platform works for allocating money, trying to minimize risks thanks to a good diversification. In this case, borrowers obtain money in short time and the platform has a high probability that every borrower gets its request of funds.

It is when each investor selects the loan, according to the information given. Investors also decide the amount to lend to each borrower. This mechanism is more similar to the traditional crowdfunding campaigns, but it is very time-consuming for investors and it does not assure the right diversification. There is also the possibility that some borrowers can be only satisfied partially, because of not being selected by any investor.

Another interest factor regards the mechanism developed to determine the interest rate applied to each loan. Milne and Parboteeah [10] classify platforms according to two alternatives: reverse auction and automatic matching. In the reverse auction, lenders set their minimum interest rate and borrower their maximum interest rate and the matching is when there is a correspondence. All investors can see it and decide for a certain interest rate to offer, knowing that the higher it is, the lower is the possibility to finance the loan, because only the lowest ones will be selected and offered to the borrower. Once the investors’ offer is selected, then the average interest rate is computed and shown to the borrower, who can accept it or not.

In the automatic matching, the platform sets the interest rates and then combine the loans according to the risk and return required by the lender. Where there are imbalances, the platform adjusts the interest rates [10].

There is also a third possibility [11], which is similar to the mechanism working in the stock market; from one hand borrowers set a maximum interest rate, and on the other hand lenders set a minimum (not on the same loan, but on all loans offered by the platform) and the platform matches compatible bids and offers.

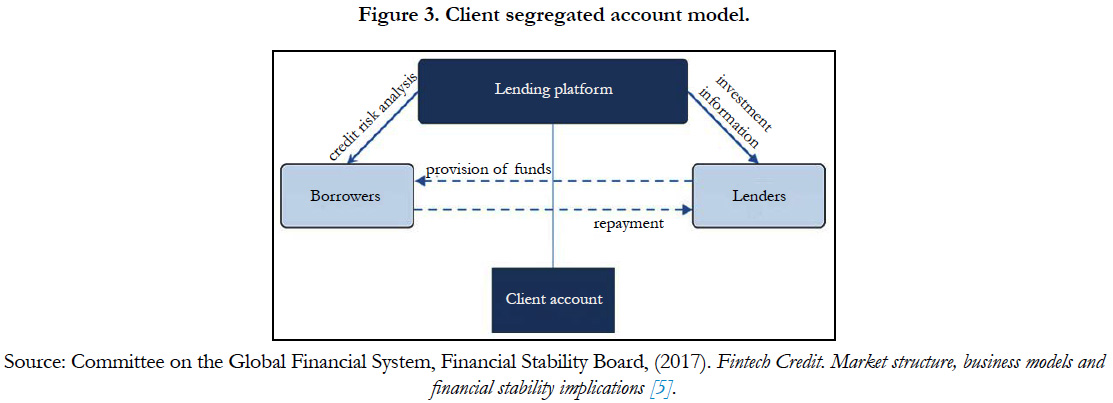

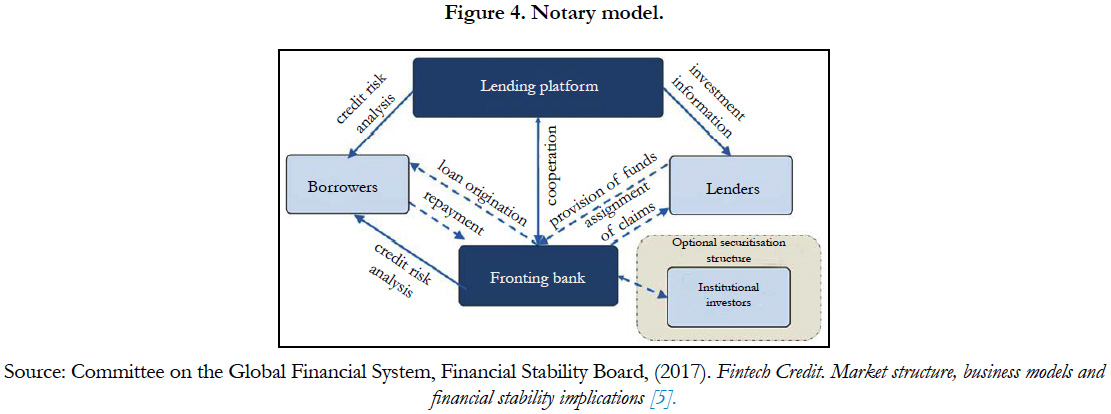

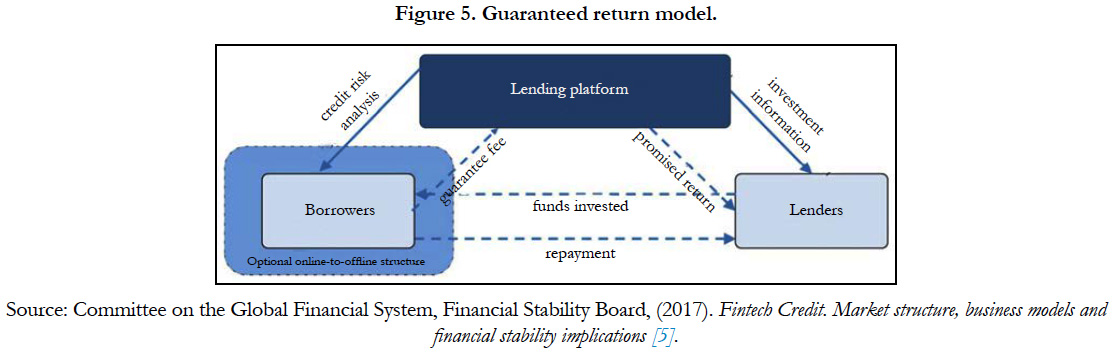

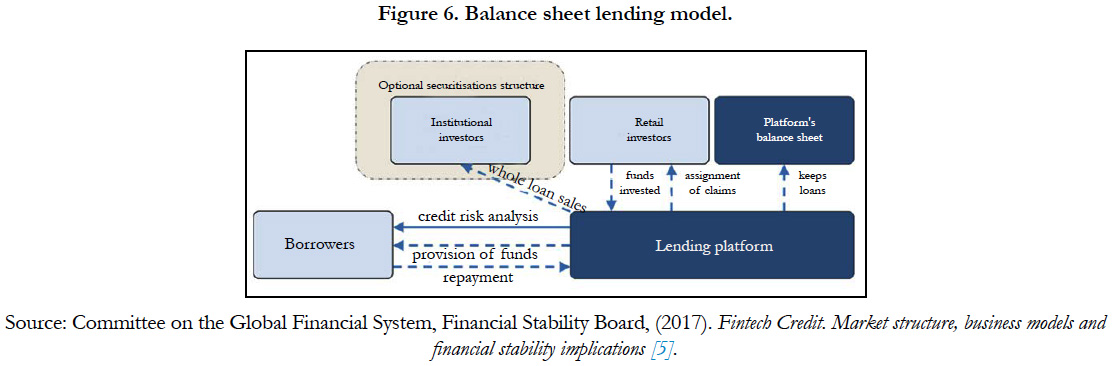

Finally, credit platform have also different ways to process the financing, and they are client segregated account model; notary model; guaranteed return model and balance sheet model.

- Client segregated account model (see Figure 3); it is when the platform matches borrowers and lenders and money is collected in accounts which constitute a separate patrimony, so that, in case the platform fails, it cannot be used to pay creditors. Financing is made using a reverse auction procedure, which can be manual or automatized. A peculiar model of this type implies they have a common fund whose quotes are on the platform by financiers.

• Notary model (see Figure 4); it is when the loan is generated by a partnering bank. Online platform only acts as a broker, connecting borrowers and lenders, and it is the bank that originates loans and sells them to investors.

- Guaranteed return model (see Figure 5); It is when the platform collects funds and applies an interest rate, which is the outcome considering the borrower’s risk and the loans features. This can be done throughout two different methods: the first one implies the research and the pre-screening of financers outside the platform; after that, the loan request is displayed on the platform website so that lenders can make their offers. This method is well widespread in China where there is an excess of supply compared to the demand. The second method requires to have an algorithm which automatically invests the funds collected. In this case, there is a remuneration depending on the rates and loan duration.

- The balance sheet model (see Figure 6); it is when the platform retains loans in their balance sheet, so that it can sell them to institutional investors, or other retail investors financing loans. In this case, the platform obtains the money from these investors and provides it to borrowers, which pays interests to the lending platform. In case of failure of the platform, investors will have difficulties to obtain their money back.

The Issue of being a Platform

The value of a platform relies in its capacity to create interactions, which are the main sources of value for it. Platforms are good at reducing search and transaction costs for participants [12].

In order to assess the concept of platform, it is interesting to take the perspective of defining pipelines first. They have been the dominant model of business, when the main business idea is that to produce something, push it out and sell it to customers. Value is produced upstream, and consumed downstream, where there is a linear flow of information, data, etc. Prior to the internet, much of the services industry ran on the pipe model, which was brought over just after the internet. This is because Internet, being a participatory network, is a platform itself and allows any business, building on top of it, to leverage platform properties. There is a different mind-set behind the two business models, because of pipe charges consumers for value created, and platform creates value and look for who to charge for that. The two models can coexist, as Apple demonstrates. In order to move from pipeline to platform three key shifts are necessary [4]:

1. From resource control to resource orchestration. The resource-based view of competition holds that firms gain advantage by controlling scarce and valuable assets. (…) With platforms, the assets that are hard to copy are the community and the resources its members own and contribute. (…)

2. From internal optimization to external interaction. Pipeline firms organize their internal labor and resources to create value by optimizing an entire chain of product activities, from materials sourcing to sales and service. Platforms create value by facilitating interactions between external producers and consumers. (…) The emphasis (…) persuading participants and ecosystem governance become essential skills.

3. From a focus on customer value to a focus on ecosystem value. Pipelines seek to maximize the lifetime value of individual customers of products and services, who, in effect, sit at the end of a linear process. By contrast, platforms seek to maximize the total value of an expanding ecosystem in a circular, iterative, feedback-driven process. Sometimes that requires subsidizing one type of consumer in order to attract another type.

Given that, competing becomes more complicated and dynamic in a platform world. The competitive forces described by Michael Porter (the threat of new entrants and substitute products or services, the bargaining power of customers and suppliers, and the intensity of competitive rivalry) still apply, but behave differently in a platform, while new factors come into play. Interactions, participants’ access, and new performance metrics become the new drivers. When managing a pipeline business the focus is on growing sales. Therefore, those goods and services delivered (and the revenues and profits from them) are the units of analysis. For platforms, the focus shifts to interactions-exchanges of value between producers and consumers on the platform. The number of interactions and the associated network effects are the ultimate source of competitive advantage, because the focus of strategy shifts to eliminating barriers to production and consumption in order to maximize value creation. To that end, platform executives must make smart choices about access (whom to let onto the platform) and governance (or “control”-what consumers, producers, providers, and even competitors are allowed to do there) [4].

Therefore, the main feature of platforms is represented by network effects, which drive demand-side economies of scale. This means that the more users join the platform the more valuable the platform becomes for each user. Throughout social networking and demand aggregation, companies can attract a higher number of customers so to increase the average value per transaction, because the larger the network, the better the matches between demand and supply. Behind this, there is a virtuous circle: the larger the network, the higher the appeal for other customers, whose presence attracts more customers. In contrast to what happens in traditional companies, for what concerns platforms, value-creating activities take place outside the company [13].

In a technological platform, each side has its own process of value proposition, capture and creation. Value proposition is addressed to complementary and interdependent customer groups; while value creation and capture need to have organized on a platform, which can connect sides and create network effects [14]. These network effects lead to demand-side economies of scale. This is because fixed costs are high at the beginning, and marginal costs are lower. Thus, the volume of transactions is very important, because if the volume is large, platforms can charge customer with a lower price. This develops a virtuous circle, since the lower the price, the bigger the volume [4].

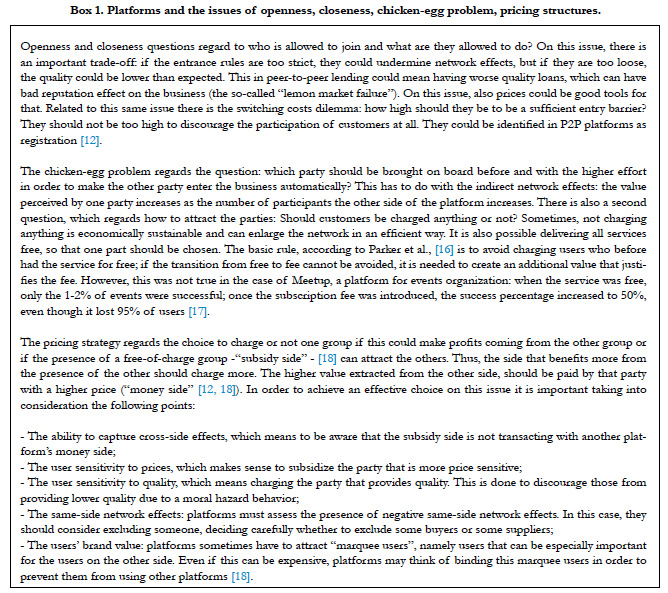

Network effects can be on the same side or can be indirect (crossside network effects). In the first case, each customer obtains a benefit when the number of customers on its side is high, while in the second case, each customer benefits from a higher number of customers in the other side [15]. There are many other factors related to platform and they are outline in Box 1.

According to Parmentier et al., [14], the success for a platform is based on the presence of the following factors:

• Provision of services for unserved customers;

• Tools able to engage customers and suppliers;

• Service reliability made possible by the computerization of the customer service;

• Continuous improvement of the offer and in understanding customers thanks to data collection.

The first factor belongs to all companies, but it is extremely important in the case of platforms, where network effects are fundamental. In addition, the identification of new customer groups to promote the adoption of the platform is fundamental because a platform has to reach a critical volume. The niches can be multiplied, then, the platform should be opened to new product/service offering. The main rule is that a large number of niche products with small dissemination generate more value than a small number of products with a wide dissemination. At this point, customers may link together, and the revenue model should be structured [14].

As stated in the previous sections, online peer-to-peer lending is a growing industry with huge potential for capturing customers from mainstream financial institutions and therefore setting a new standard for loan requests and for creating an additional investment opportunity. To get some benefits from this growth, companies operating in this industry should develop a resilient business model that aims at attracting the greatest number of lenders out of the whole lenders’ population and the greatest number of borrowers out of the whole borrowers’ population. This is because the more you attract customers, the more you extract value from them. Two important assumptions are worth to be outlined at

this stage:

As in all economic scenarios, in order to reach an equilibrium, demand for a good or service needs to equal the supply of the same good or service. This relationship is even more important.

When it is to consider the online peer-to-peer lending communities. In fact, demand for capital to be borrowed needs to be satisfied by supply of capital to be lent and demand for return on capital lent needs to be satisfied by supply of return on capital borrowed. If a business model is biased toward lenders or borrowers, there will be a mismatch between demand and supply, which could create dissatisfaction among users who could see, respectively, their loan requests not fulfilled or their demand for return on investment not satisfied.

This is because of network economies, which are an extremely important factor for online communities and peer-to-peer lending, which is not excluded from this paradigm. Especially when this market segment is at its start-up stage, the issue of attracting both borrowers and lenders is of extreme importance, so to be able to lock them-in in the community since the beginning, therefore increasing the potential number of users in the community, which also increases the market share of the company. This may happen thanks to the feedback effect, which increases the attraction of new borrowers and lenders. Additionally, due to density economies, the higher the number of borrowers and lenders, the more intensively the firm resources are utilized and the lower the unit costs per user incurred to set up the business activities. Once both the population of borrower and the population of lenders are attracted in the network, there is a lock-in effect, influenced by three important factors, one naturally implicit in peer-to-peer loan contractual schemes and two that area consequence of human nature:

Loan contract: once a loan contract is stipulated, both borrowers and lenders enter into an agreement lasting for a prolonged period of time (inmost of the cases three years) whereby the lenders hand over a certain amount of capital to borrowers. On the other hand, borrowers commit themselves to monthly payments of principal and interest back to borrowers. Since this relationship is supposed to last for the whole length of the loan, it is in both borrowers and lenders interest to stay within the community. Lenders need to recover the money they gave away in the first instance; borrowers instead need to return money so as to avoid big consequences on their credit history or even judiciary actions.

Favourable financial conditions: Unless their loans default, lenders will find it interesting to see that their investment was successful and that they managed to earn a good return, anyway, while doing a good deed to the society. Therefore, it will be a normal attitude to undertake other loans and therefore being locked-in the community for an even longer period. It is important to notice that some online peer-to-peer lending communities actually feature an auto-lending tool as a standard function: once the borrowers repay their monthly rates to lenders, this money is allocated to new borrowers requests automatically, which satisfy the requirements of the lender. Crucial in this continuous lending procedure is the risk of default that a lender incurs, which must obviously be low. While this perpetual relationship between the lenders and the platform could be a good natural strategy to lock-in customers, this cannot be true for borrowers. In this regard, borrowers tend to be one time demanders of a peer-to-peer loan. However only time will prove if this phrase is correct; infact, considering all peer-to-peer lending platforms most of the loans have not yet reached maturity and in most of the platforms it is not possible to ask for two loans at the same time. For this reason, before inferring a borrower habit, it would be advisable to wait until most of the loans in the industry have been paid back and borrowers ask new loans. A logical assumption would be that if borrowers manage to find financing on an online community at a rate that is much lower than what they could receive in their closest alternative, they will surely revert back to peer-to-peer lending incase of future financial needs. However, this is not a sequential process as this “come-back” is strictly dependent on the financing needs of the borrower.

Concept commitment: In the financial world, the brand is an extremely important asset, as the customers usually perceive it as a sign of professionalism and safety of the financial institution (“brand stickiness”). Now, however, it is too early for customers to show a true commitment to a certain platform brand given the relatively young age of this phenomenon. What customers are already showing, however, is a strong commitment to the concept of “peer-to-peer lending” as they assume that this is a more transparent and social way of transacting money, than what offered by mainstream financial institutions. This commitment to the concept creates a natural lock-in effect that platforms will be able to exploit once the lock-in effect, explained so far, is in place; the peer-to-peer platform is in a perfect condition to extract economic value from both lenders and borrowers [19]. So far, the company has simply attracted borrowers and lenders to the platform and has earned a fee from the subscription of these users, granting them the possibility to use the platform to lend and borrow money.

Given that, there is big earnings potential that can be obtained from selling products and services complementary to the loans the borrowers receive or to the investment the lenders make.

To prove this, according to Ziegler et al., [20] it is outlined that alternative finance models that generate larger volumes are also those which report the most significant changes to their product offerings and business models. The converse is applicable to models associated with lower volumes.

Therefore, two vectors become important and critical for this business, and they are attractiveness for borrowers and attractiveness for lenders as these two basic indicators define a successful P2P business model, capable of attracting and locking-in users.

Conclusions and Managerial Implications: The Platform Dilemma

Looking at P2P lending platforms, one of the strength points is lower rates for borrowers and higher rates for investors; this can work overall in comparison with banks but not with other competitors necessarily. In fact, the price lever is difficult to use to compare platforms, because it would lead to different set of commissions, which are the bigger source of revenues, but overall price competition has not to become the lever to compete in the market. Otherwise, it could face the same “end” as some areas of the retail banking business have been experiencing for some time, because they are perceived to be commodities by customers, which think of them being similar apart from the price that has become the main competitive lever in the market [21].

Given that, differentiation could be the right strategy for a platform both to attract and retain customers, overall because there is the assumption that peer-to-peer lending platforms, in order to be successful, need to have both a balanced demand/supply of capital (demand should equal supply in each economic relationship). Platforms also need to have a high number of lenders and borrowers (in order to exploit both the positive feedback effects characterizing social networks, and density economies, which go in the same direction of lowering costs). All this above is required because attractiveness for lenders and borrowers are the main issues to manage for platforms. Given that, taking care of customers first is likely to become the biggest driver for Fintechs, and specifically within the online lending market, which have to take care of consumers, as they have become both the lenders and the borrowers.

The growth of online lending will accelerate in the next years [22], under certain conditions, and this can be true if they take care of both investors and borrowers’ needs. Notwithstanding, it must be underlined that the engine for platform to be profitable is based on the capacity to keep the credit risk low and a slim cost structure with a stable source of recurring revenues. Infect, these companies would not long survive if the “fin” part of the product is neglected. If a company failed to observe good credit risk process decision and poor lending practices, for example, these products - and with it the companies - would fail.

Moving back to focus on investors, it has been observed the need for them to hold liquid assets so that the organization of secondary markets for online loans is emerging in the industry. Assets have to be liquid and costs free for them. On the same side of investors, there is the strategic opportunity to differentiate the platform, especially in markets where there is a fierce competition or there is a higher fragmentation. Given that, the next step, we are already experiencing in the market, is the emerging and interesting idea of re-bundling, which will give birth to at least some major consumer products innovation, which are going to satisfy both lenders and borrowers. This is becoming a critical issue otherwise, even though online lending has become an interesting and success story, this is going to be not because of the advent of a new financial product, but rather through making an old, in-demand financial services product more accessible to consumers. The products on offer and the types of loans available through these platforms still very closely resemble the more traditional loan types, with the online accessibility and speed of access being the main differentiators. Only over the last two years has the UK seen some “newer” products to trade in the platform such as the Innovative Finance ISA (https://innovativefinanceisa.org.uk/), but P2P lending platforms need to upgrade their value proposition. We think that this can be done also developing a strategy of re-bundling, which stands behind the idea that suggesting one-product, volume-driven online providers would gradually develop broader product ranges and therefore more opportunities to create profitable relationships with their customers. Therefore becoming a multi-product company is a strategy that online marketplace lenders can decide to perceive, such as the move done by Goldman Sachs’s platform, Marcus, to purchase the personal money management app Clarity Money, which may represent an acknowledgement that Marcus needs to create deeper relationships with customers across more products. This underlines the need to have a clear strategy before any choice of buying or making new business units internally. In the case of Goldman Sach’s, the main idea behind may that of putting together credit education and monitoring, which could develop a strong engagement for customers to stay in the market. What is important to underline here, is that it is not like buying another company to integrate in the platform, but every choice must be integrated and link strictly to the previous steps also having a clear vision about the next steps to develop, but each one has to get going itself.

Strategic decisions like that of re-bundling lie behind the critical issue to manage, which is that developing a building blocks approach in online lending is the beauty side of being a platform, but in order to keep going from good to great it has to be implement without underestimate the risk to let prevailing a pipeline culture. In my opinion, this is going to be the platform dilemma. The risk is not in the early stage, when you have gone a step further, but it is later when players could deny the essence of being a platform. The fact that consumers hold the power to more significantly influence the financial products available to them, along with the ever-evolving way in which they are delivered, will surely lead to an extremely interesting period of financial services development. As always happens, changes in dynamic will lead to other changes, which will not only pose new challenges for Fintech companies and the financial sector as a whole, but will also likely raise some very interesting questions and challenges for the regulators of these markets around the world. These challenges, among others, will be those in terms of business models’ resiliency; customers’ transparency and sustainability; and market liquidity. All this above takes us to the next frontier in financial services, which is that of establishing Open Ecosystems. The market has experienced that closed systems do not scale or may implode. Marketplace lending needs to be ubiquitous. To do this, they must maintain an open dialogue, educate and share information with their stakeholders and create a broader understanding of both platforms and products, because the main rule is that change is inevitable. Notwithstanding the industry has not to lose sight of its important goals: to give people access to affordable credit, as well as putting them in the condition to sustain it. Therefore, if the change is inevitable, it is always required to look for a certain amount of resilience.

Given all that above, it is also interesting to conclude with some ideas on the relationships between P2P lending platforms and the framework of the next Basle IV agreement on banks’ stability. Apart from the debate between US and European banks in terms of the way they approach the credit risk calculation for their Risk Weighted Assets (RWA), it is interesting to outline that the situation is not going to be homogeneous in the market. Different banks with different assets and liabilities structures will be impacted differently. It is said that there is going to be an increased need of capital for certain banks, given their present credit portfolio, while others could benefit from the new situation.

I could expect to see some more requests moving towards the P2P platforms because of many reasons, such as more selected banks’ credit processes, a reduction on some forms of credit, a different allocation between business and retail customers, an increased requests of covenants, etc. But I think that this will depend overall on the strategic decisions banks will take at present. I also think that according to what has been outlined before an increased number of borrowers and lenders will benefit the P2P platforms, but in order to make them more resilient and increased specialization and credit selection could be useful also to develop their reputation and customers’ trust, which are both linked to the way they manage their risks. I think this last point is going to be mandatory overall if the credit decisions in banks will be more selective, given the above constraints. Otherwise we could find that some P2P lending platforms are going to face the lemon market problems if they do not develop effective proprietary credit risk assessment and management approaches. I think that credit bureau information might not be effective enough for them in future also because new borrowers will enter the market. Given that, platforms’ development and reputation will depend overall on their ability to reduce credit risks and keep a lean cost structure organization, which could also benefit from a diversification of the range of services offered, as outlined before.

References

- Arner DW, Barberis J, Buckley RP. The evolution of Fintech: A new postcrisis paradigm. Geo. J. Int'l L. 2015;47:1271.

- Blake M, Vanham P. Five things you need to know about fintech. World Economic Forum. 2016 Nov 30.

- PwC. What is Fintech?. 2017.

- Van Alstyne MW, Parker GG, Choudary SP. Pipelines, platforms, and the new rules of strategy. Harv Bus Rev. 2016 Apr 1;94(4):54-62.

- Committee on the Global Financial System, Financial Stability Board. Fintech Credit: Market structure, business models and financial stability implications. 2017 May 22.

- Hossain M, Oparaocha GO. Crowdfunding: motives, definitions, typology and ethical challenges. Entrepren Res J. 2017 Apr 1;7(2).

- European Commission. Crowdfunding in the EU Capital Markets Union, Report, Commission Staff working document. 2016.

- Mo S, Chen KC, Ye C. The Evolving Role of Peer-to-Peer Lending: A New Financing Alternative. J Int Acad Case Stud. 2016 May 1;22(3).

- Ziegler T, Shneor R, Garvey K, Wenzlaff K, Yerolemou N, Rui H, et al. Expanding Horizons: The 3rd European Alternative Finance Industry Report. NY: University of Cambridge; 2018. p. 23.

- Milne A, Parboteeah P. The business models and economics of peer-to-peer lending. Euro Credit Res Inst. 2016.

- Financial Stability Board. Committee on the Global Financial System. 2017 May 22.

- Hagiu A. Strategic decisions for multisided platforms. MIT. 2014 Jan 1;55(2):71.

- Van Alstyne M, Parker G. Platform Business: From Resources to Relationships. GfK Market Intel Rev. 2017 May 1;9(1):24-29.

- Parmentier G, Gandia R. Redesigning the business model: from one-sided to multi-sided. Journal of Business Strategy. 2017 Apr 18;38(2):52-61.

- Gandia R, Parmentier G. Optimizing value creation and value capture with a digital multi‐sided business model. Strategic Change. 2017 Jul;26(4):323- 31.

- Parker GG, Van Alstyne MW, Choudary SP. Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy and How to Make Them Work for You. WW Norton & Company; 2016 Mar 28.

- Hagiu A, Rothman S. Network effects aren’t enough. Harv Bus Rev. 2016;94(4):17.

- Eisenmann T, Parker G, Van Alstyne MW. Strategies for two-sided markets. Harv Bus Rev. 2006 Oct 1;84(10):92.

- Hulme M, Wright C. Internet based social lending: Past, present and future. Soci Future Observe. 2006

- wikipedia.org [Internet]. Mackenzie Ziegler; Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. ([cited 16 September 2018 ]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Mackenzie_Ziegler

- Omarini A. Retail Banking. Business Transformation and Competitive Strategies for the Future. Palgrave MacMillan Publishers, London. 2015.

- Zhang B, Wardrop R, Ziegler T, Lui A, Burton J, James AD, Garvey K. Sustaining Momentum: The 2nd European Alternative Finance Industry Report. Camb Cent Alter Finance. 2016;120.